God exists, from pure reason?

God exists, from pure reason?

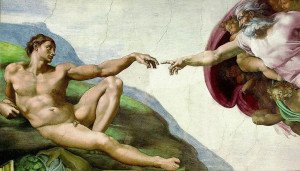

The idea of a creator God is the belief that He is the source of all creation. We spend a lot of time with the question of how science and religion should be employed to seek answers about God’s existence and essence. Ted Peters addresses this concern in his article, Techno-Secularism, Religion, and the Created Co-Creator. He writes that it is not our place as religious men to push away science or try to otherwise undermine it. He states, “Christian ethics is born out of the Bible’s promise of the new that is to come, not out of protecting or preserving the old in its inherited and unredeemed state” (484). This state is one in which he argues, science can serve to redeem, or rather, shed light upon the world. Men should not attempt to prevent science from investigating the truths of the Bible, in some effort to protect it from scrutiny, or preserve its historical interpretation for the faithful.

As we face down the challenge of techno-secular society, we dare not shrink back and abandon all science and all technology to the secular sector or run like frightened dogs with our religious tails between our legs. Rather, we need to lift up the fact that scientific study and technological innovation belong to our human nature, a human nature created and inspired by God (848). Fair enough. But aren’t we acknowledging that God exists, and aren’t scientists doing the same, when we argue about God? After all, how can we argue in such profound detail, about something which encroaches on almost all aspects of our lives, if such a thing does not exist as any part of our reality?

I champion the idea of God’s existence from the science of secular reason, on several grounds. In this article, I will address only one, an Ontological Argument of sorts. The Ontological argument itself, as presented by Anselm, is based simply upon the fool’s declaration. Anselm demonstrates instability between the two statements; that one understands the claim that God exists, and that one does not believe in God. Descartes explores this issue, and its primary criticisms in his meditations. Taking these ideas, I assert that the logic below, being my twist on the work of greater philosophers than myself, serves as a modern argument from reason for the existence of God today.

Try to imagine something that does not exist. You might first imagine a glass of water on a shelf, or a slug surfing in the bay atop an Oreo cookie. OK, but I assert that you cannot imagine anything at all without using some notion of things you already know. So, start to imagine now, but keep in mind that whatever you imagine cannot have a shape, because you already know about shapes. Indeed it cannot have a size or a color, or exist in time or take up space. It cannot have a name, and it cannot possess any values, not even truth statements about its own existence, because “truth” is a pre-existing condition, a reference to logic, which is indeed something you already know. What is it that you have imagined? How can you relate it to me or explain what it is, for it has no name, logic, shape, size, time, color, or any other value you know whatsoever? It is inconceivable.

The concept of God is that of a “Supreme Being.” It must be true that if He is indeed “supreme,” then He must exist. A “Supreme” Being must have to exist everywhere. This principle might be easier to understand this way; something which is supreme cannot be limited – and to say that it does not exist is a limit to its supremacy. Put even more simply, something that exists is more perfect than something which does not exist. Therefore, if something does not exist, it is imperfect, and as such, it cannot be the Supreme Being. This is not in question.

If it is true that one’s mind can only conceive of things related to what already exists, as is made obvious by our inability to imagine anything without referencing things which already exist, then because we can conceive of God, it must be true that God possesses the property of being relative to what already exists. To possess a relative nature to other items in existence, He needs to exist somewhere. Moreover, since we can conceive of God as a being, of which no greater being can be conceived, then as a “Supreme Being” He must exist in all possible worlds, even in your living room. Therefore, it can only follow from absolute logic, God exists in our world.

“Not so fast,” say s the naysayer. “This argument merely states that an idea exists. An idea is not the same as reality. It’s one thing to say I can conceive of God, and quite another to say He must exist because I can conceive of Him as a Supreme Being.” Really? Is that what the Ontological argument holds? What kind of thing that does not exist is able to have such definition as we have when we speak of God? What kind of thing that does not exist is so evocative and relative to the lives of millions who profess a profoundly personal relationship with God? What kind of thing, which does not exist, is so ingrained in worldviews? What kind of mere idea is so powerful, yet exists as no reality whatsoever? Would we make the same claim, that love does not exist, because it is a mere concept–something millions of people claim to feel?

s the naysayer. “This argument merely states that an idea exists. An idea is not the same as reality. It’s one thing to say I can conceive of God, and quite another to say He must exist because I can conceive of Him as a Supreme Being.” Really? Is that what the Ontological argument holds? What kind of thing that does not exist is able to have such definition as we have when we speak of God? What kind of thing that does not exist is so evocative and relative to the lives of millions who profess a profoundly personal relationship with God? What kind of thing, which does not exist, is so ingrained in worldviews? What kind of mere idea is so powerful, yet exists as no reality whatsoever? Would we make the same claim, that love does not exist, because it is a mere concept–something millions of people claim to feel?

For the secularist with an agenda, one who will stay glued to even the most improbable notions (grasping any weak justification to reject the existence of God), little can be said or done to prove His existence. Such a person would reject His presence at the dinner table. After all, none are so blind as those who will not see. But for the rest of us, the Ontological argument immediately presents us with a clear understanding, lex parsimoniae, that people who deny the existence of God, from rational thought, must do so while jumping through many intellectual hoops, sifting for a needle in a haystack they deny the existence of.

Anselm’s actual argument reads, “Then is there no such nature, since the fool has said in his heart: God is not? But certainly this same fool, when he hears this very thing that I am saying – something than which nothing greater can be imagined – understands what he hears; and what he understands is in his understanding, even if he does not understand that it is. For it is one thing for a thing to be in the understanding and another to understand that a thing is (Proslogium).

Citations:

Peters, Ted. “Techno-Secularism, Religion, and the Created Co-Creator.” Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science 40.4 (01 Dec. 2005): 845-862. Philosopher’s Index. EBSCO. [Library name], [City], [State abbreviation]. 21 Apr. 2009 <http://library2.iusb.edu:2058/login.aspx?direct=true&db=phl&AN=PHL2080368&site=ehost-live>.

Steinberg, Jesse R. “Leibniz, Creation and the Best of All Possible Worlds.” International Journal for Philosophy of Religion 62.3 (01 Dec. 2007): 123-133. Philosopher’s Index. EBSCO. [Library name], [City], [State abbreviation]. 21 Apr. 2009 <http://library2.iusb.edu:2058/login.aspx?direct=true&db=phl&AN=PHL2122051&site=ehost-live>.

Kant, I. (1978). Lectures on philosophical theology, tr. A.Wood & G. Clark. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- “Anselm (1033-1109): Proslogium.” Medieval Sourcebook. 1998. Fordham University. <http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/anselm-proslogium.html>.