Moral relativism is the idea that what is right for me might not be right for you. It means that everyone can decide what is right and wrong. It’s tempting to believe in moral relativism, especially when faced with a moral dilemma like abortion or euthanasia. It is terribly hard for some people to imagine that the same standard of right and wrong applies to everyone in all circumstances. Our culture reinforces moral relativism all the time, in all types of touchy subjects. We are barraged with the idea that there are no absolutes—there is no true right and wrong, only what’s right or wrong based on the circumstances and personal viewpoints of those involved. At some point in your life, have you ever asked, “Is this true?”

is the idea that what is right for me might not be right for you. It means that everyone can decide what is right and wrong. It’s tempting to believe in moral relativism, especially when faced with a moral dilemma like abortion or euthanasia. It is terribly hard for some people to imagine that the same standard of right and wrong applies to everyone in all circumstances. Our culture reinforces moral relativism all the time, in all types of touchy subjects. We are barraged with the idea that there are no absolutes—there is no true right and wrong, only what’s right or wrong based on the circumstances and personal viewpoints of those involved. At some point in your life, have you ever asked, “Is this true?”

People who believe in moral relativism hold two basic claims, each of which must be true in order for them to hold their relativist viewpoints: (1) There is no absolute truth. (2) There is no absolute moral law. It makes perfect sense because if there is absolute truth, then moral dilemmas become very scary. An absolute truth means there is a right answer, yet different people in the same situation make different choices, so absolute truth would mean some of them were wrong for the choices they make. A moral relativist cannot accept that people are wrong, so they simply set aside the notion that truth can be an absolute. The same is true of moral law. For the relativist, no moral laws are broken when people are faced with moral dilemmas. If they accept the notion of an absolute moral law, then they would be held to that law—and that’s truly unacceptable. Moreover, others who make choices would fall into two groups, those who made the morally right choice and those who made a morally wrong choice; this is equally unacceptable under moral relativism.

It takes very little logic to realize that truth is absolute, and that there is an absolute moral law. If Steve participates in a riot, stepping over a wounded storeowner to loot some goods, he employs moral relativism to justify his actions. He imagines it is not absolutely wrong to loot because some other notion helps Steve justify his actions. If we imagine Steve is angry with the police, or mad about not having a job, weary of a life of poverty, or he is simply disenfranchised in any number of ways, the n a moral relativist might say Steve was justified in looting, or at the very least, it was the right decision for him based on his unjust situation. But it only takes turning the situation around to know moral relativism is wrong.

n a moral relativist might say Steve was justified in looting, or at the very least, it was the right decision for him based on his unjust situation. But it only takes turning the situation around to know moral relativism is wrong.

When we imagine Steve’s belongings are looted, do we also imagine that Steve is fine with it? What if the thief were disenfranchised in whatever way Steve was disenfranchised? Do we imagine that Steve would applaud his belongings being stolen? Would he shake the hand of the looter, assuring him/her that looting was the right thing to do? Would Steve accept someone stepping over his wounded body to steal from him? After all, a true moral relativist would understand–he would believe that failing to help someone who was wounded, and even looting a wounded man was no more morally wrong than any other decision.

It takes very little insight to know Steve would not applaud being left to suffer while being looted. This means Steve knows in his heart that there is a moral law, a right and wrong, and that he simply chose to act immorally. Moral relativism is wrong. The moral law is undeniable, and while it’s often difficult to view the moral law properly because of moral dilemmas resulting from competing wants, it’s very easy to discern moral laws based on our reactions when a scenario is turned around.

Abortion is a difficult issue for many people. Moral relativism imagines there are competing interests. The mother is inconvenienced by an unwanted pregnancy. Her body plays host to the development of a child before birth, and in the latter months of her pregnancy, it can be downright uncomfortable. Being pregnant might deprive the expectant mother of some pleasures she wants. She cannot drink, do drugs, smoke, and she might miss out on some other pleasures she enjoys.

Abortion is a difficult issue for many people. Moral relativism imagines there are competing interests. The mother is inconvenienced by an unwanted pregnancy. Her body plays host to the development of a child before birth, and in the latter months of her pregnancy, it can be downright uncomfortable. Being pregnant might deprive the expectant mother of some pleasures she wants. She cannot drink, do drugs, smoke, and she might miss out on some other pleasures she enjoys.

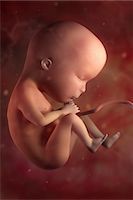

Some expectant mothers are OK with abortion. They don’t value the pleasure a child would bring to their life as much as they concern themselves with how an unwanted pregnancy might cost them money, time, career opportunities, etc. Like moral relativism that claims there is no truth, abortive mothers claim there is no baby. That takes a great deal of intellectual jumping through hoops—after all, if you do nothing, it’s not a blueberry muffin that is birthed into the world, it’s undeniably a baby.

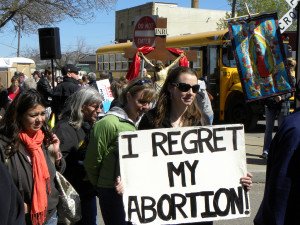

There are many reasons an expectant mother imagines she would want the results of her pregnancy scraped out and discarded. Moral relativism leaves plenty of room to accept abortion. In fact, many moral relativists claim they would not get an abortion themselves, but feel that others who make that choice are not morally wrong, because everyone can decide for himself or herself what is right and wrong. This is the height of relativism. It’s wrong for me, but right for you if you think it’s right.

Again, the moral law is easy to uncover when the tables are turned. Imagine the same woman, Susan, is a typical well-adjusted individual who is suddenly transported back in time for a talk with her own pregnant mother who is considering aborting Susan. If her mother decides to abort, Susan will never have existed outside the womb. She will never have made friends, enjoyed pizza, or experienced sex. She will never have played as a child, never have known her family, made friends, supported her mother through tough times, gotten married, and all her dreams would never have been imagined. It will be as though she never existed in the lives of those she loves. It’s unlikely that Susan would be indifferent to her mother’s decision, saying, “Whatever you decide is the right thing to do because it’s right for you and it has nothing to do with me.” In reality, she would not encourage her mother to abort, no matter how her mother tried to justify it. You might notice that all the people who support abortion are people who were born. Even if you imagine this example is flawed because Susan would never have known the difference, it’s easy to see that her mother is making a decision that effects Susan whether Susan knows it or not. To say a pregnant mother takes nothing away from her developing child by discarding her is ignoring the obvious.

Again, the moral law is easy to uncover when the tables are turned. Imagine the same woman, Susan, is a typical well-adjusted individual who is suddenly transported back in time for a talk with her own pregnant mother who is considering aborting Susan. If her mother decides to abort, Susan will never have existed outside the womb. She will never have made friends, enjoyed pizza, or experienced sex. She will never have played as a child, never have known her family, made friends, supported her mother through tough times, gotten married, and all her dreams would never have been imagined. It will be as though she never existed in the lives of those she loves. It’s unlikely that Susan would be indifferent to her mother’s decision, saying, “Whatever you decide is the right thing to do because it’s right for you and it has nothing to do with me.” In reality, she would not encourage her mother to abort, no matter how her mother tried to justify it. You might notice that all the people who support abortion are people who were born. Even if you imagine this example is flawed because Susan would never have known the difference, it’s easy to see that her mother is making a decision that effects Susan whether Susan knows it or not. To say a pregnant mother takes nothing away from her developing child by discarding her is ignoring the obvious.

We already know what the moral law is. It’s the same for everyone, even those who want it to be otherwise when it conflicts with their personal desires. Life carries with it a special value. Remove all the fancy labels and distracting language, and we all know a pregnant mother has a developing baby inside her (it’s not a muffin or simply some kind of goo). No matter what stage of development she is in, it’s a developing baby. If you can’t bring yourself to admit that, just look up the stages of human development in a medical book; you can easily trace it back to the moment of conception (because we’re talking about humans).

There are plenty of other arguments to muddy the waters. Moral relativism works best when dilemmas  are as complicated as possible. The more competing values exist, the more rational their relativism seems. Some ask, “What if Susan was poor?” or “What if Susan was born with Down Syndrome?” … “Wouldn’t it be better if Susan never existed?” The problem with this tactic is that it could never be the case that Susan never existed. Such a question ignores the fact that at the moment of conception, she does exist. A mother cannot be a little bit pregnant. Either she is pregnant or not. If she is pregnant, then what she is pregnant with exists, and each hour she is an hour older, an hour further into her life cycle, like we all are. We are all at some point in our life cycle, and Susan happens to be at the beginning. The question is not whether she exists; it is whether it is morally permissible to deny her a future–her mother has already grown beyond Susan’s stage of life, and is in the legal position to choose between allowing Susan the same opportunity or preventing Susan’s entire future in lieu of some other competing desire the mother has at the time.

are as complicated as possible. The more competing values exist, the more rational their relativism seems. Some ask, “What if Susan was poor?” or “What if Susan was born with Down Syndrome?” … “Wouldn’t it be better if Susan never existed?” The problem with this tactic is that it could never be the case that Susan never existed. Such a question ignores the fact that at the moment of conception, she does exist. A mother cannot be a little bit pregnant. Either she is pregnant or not. If she is pregnant, then what she is pregnant with exists, and each hour she is an hour older, an hour further into her life cycle, like we all are. We are all at some point in our life cycle, and Susan happens to be at the beginning. The question is not whether she exists; it is whether it is morally permissible to deny her a future–her mother has already grown beyond Susan’s stage of life, and is in the legal position to choose between allowing Susan the same opportunity or preventing Susan’s entire future in lieu of some other competing desire the mother has at the time.

Practitioners of moral relativism often object strongly when people write about abortion and give the developing baby a name or a gender. Names and genders make it hard for them to deny it’s a baby. What do they think is going to come out of the pregnant mother someday? They want so desperately to use clinical language that helps them separate from the reality that a pregnant mother is carrying a human being at some stage of development. It’s not goo. It’s a developing baby. Their denial is only supported by the feeble scaffolding of moral relativism. The thin supports threaten to change or crumble, and must be fiercely defended against all attacks or denial becomes impossible. Some people get downright mad about the language because it brings up deep-rooted truths they try to hide from themselves. Remember, by denying there is an absolute moral law, suddenly the weak arguments seem to have more power. By denying there is an absolute moral law to compare our actions to, we can imagine any moral value for any action that suits us. If they admit there is an absolute moral law, then they are bound by that law and can no longer do whatever they want. Suddenly they would have to do what’s right, even when it’s as inconvenient as having a baby. They need to object to the word baby because it’s too obvious, and far too difficult to build a lie around.

The relativist asks, “What if the mother was raped?” or “What if the pregnancy was incest?” The intended effect is that by inventing emotionally charged scenarios, arguments from moral relativism hope to show that abortion is the better of two difficult situations. It’s an effective technique to distract people from the moral law, to make it seem like what is right has suddenly become wrong. But the problem with this technique is that those who think logically are not fooled into believing the lessor of two difficult decisions is the same as the lessor of two evils. Having a baby is harder, even emotionally difficult in cases of rape, etc. But having a baby is not evil, it’s merely difficult in one way or another. Aborting a baby is less difficult but morally wrong—just ask Susan, or anyone who was born into such circumstances and grew up.

The relativist asks, “What if the mother was raped?” or “What if the pregnancy was incest?” The intended effect is that by inventing emotionally charged scenarios, arguments from moral relativism hope to show that abortion is the better of two difficult situations. It’s an effective technique to distract people from the moral law, to make it seem like what is right has suddenly become wrong. But the problem with this technique is that those who think logically are not fooled into believing the lessor of two difficult decisions is the same as the lessor of two evils. Having a baby is harder, even emotionally difficult in cases of rape, etc. But having a baby is not evil, it’s merely difficult in one way or another. Aborting a baby is less difficult but morally wrong—just ask Susan, or anyone who was born into such circumstances and grew up.

Ask an adult who was the product of rape or incest if they would rather have been aborted. The answers are the same. Any well-adjusted person would answer equally. They value their lives. We don’t try to discover moral answers by imagining how a crazed lunatic would answer, or how someone who suffers from depression would answer. We ask ourselves, “How would a typically well-adjusted individual react if a moral dilemma were turned in the other direction?” This simple technique will help you discover a moral law. It won’t be obscured by clever arguments and distracting language. It will become obvious. Why? It is because there are absolute values of right and wrong, and absolute moral laws. The actual arguments from moral relativism are not particularly clever or convincing. They are easy to see through if you simply turn them over to see what is hidden beneath all the emotionally charged rhetoric.

Moral relativists have a particularly hard time balancing their views while practicing moral relativism.  They are constantly shifting throughout their lives, always maintaining there is no absolute moral law and no absolute right and wrong. Consider asking a moral relativist which is morally worse, rape or incest. Undoubtedly, they will have some opinion about which is worse. You could give them whatever example you want. The very fact that they derive one moral claim is worse than any other is an admission that moral relativism is invalid. The only way to derive which is morally worse is by comparing both to a third standard we call the absolute moral law. Whichever is further from the absolute moral law is worse. The same is true of abortion arguments, or any two moral claims. Moral relativism cannot claim any moral claim is worse than any other without another standard by which to measure them.

They are constantly shifting throughout their lives, always maintaining there is no absolute moral law and no absolute right and wrong. Consider asking a moral relativist which is morally worse, rape or incest. Undoubtedly, they will have some opinion about which is worse. You could give them whatever example you want. The very fact that they derive one moral claim is worse than any other is an admission that moral relativism is invalid. The only way to derive which is morally worse is by comparing both to a third standard we call the absolute moral law. Whichever is further from the absolute moral law is worse. The same is true of abortion arguments, or any two moral claims. Moral relativism cannot claim any moral claim is worse than any other without another standard by which to measure them.

If you ask a moral relativist which is worse, abortion or robbery, the moral relativist can answer even though they are comparing two very different moral evils. If there were no absolute moral law, then two very different things could never be compared to each other. The relativist would have one standard for abortion and another for robbery but no independent standard by which to measure. Even so, if you ask a relativist which is worse, they will undoubtedly answer one or the other because they claim moral relativity out of convenience, in order to live as they wish, but it only works if the absolute moral law they deny actually exists. They leverage the absolute moral law when it’s necessary to prevent their weakly supported morality from turning into nonsensical gibberish.

One does not really need to compare two moral claims to uncover the truth that there is an absolute moral law. One need only to consider the notion of justice. Without an absolute moral law, there would be little to no way to know if something was just or unjust. Remember, we recognize an absolute moral law most easily when we consider how people react. The fact that we know we are being treated unjustly demonstrates that we have an understanding of the absolute moral law. If someone beat you severely without reason, you probably know you have been treated unjustly. Just as a woman cannot be a little bit pregnant, justice cannot be a little bit unjust. It is either justice or injustice. The immediate knowledge that you have been treated unjustly disrobes moral relativism and reveals the absolute moral law.

One of the greatest points of confusion in matters of relativism is the “is / ought” problem. Societal norms and shifting moral platitudes are based on what we observe in the world. This is the “is” part of things. The law permits abortion, people do it, and most people look the other way. This is how things actually are today. The moral relativist cherry-picks whatever best supports his or her wishes. This often means taking the “is” without considering the “ought.” Societal norms change, and the “is” shifts this way and that, but how things “ought” to be never changes. It is timeless and firm. The “ought” is the absolute moral law.

One of the greatest points of confusion in matters of relativism is the “is / ought” problem. Societal norms and shifting moral platitudes are based on what we observe in the world. This is the “is” part of things. The law permits abortion, people do it, and most people look the other way. This is how things actually are today. The moral relativist cherry-picks whatever best supports his or her wishes. This often means taking the “is” without considering the “ought.” Societal norms change, and the “is” shifts this way and that, but how things “ought” to be never changes. It is timeless and firm. The “ought” is the absolute moral law.

If I were a Nazi in WWII, then on any given day it “is” the case that killing Jews is both legal and encouraged. However, the absolute moral law never changes. It ought to always be wrong to kill someone because they are Jewish. Another example, abortion “is” legal today. However, once someone exists, he or she “ought” to be allowed to live. The absolute moral law is how things ought to be. It is the same for everyone at all times and in all circumstances. It never changes.

As a college student studying philosophy, I was presented with various moral arguments—spectacular moral dilemmas. One of my professors, a brilliant philosopher named Mahesh, was particularly talented in this regard. He could make even the staunchest pacifist admit that she would kill a man to save a busload of kids, or torture a prisoner to end the torture of a million helpless innocent schoolchildren crying for their mothers. One scenario was more gruesome than the next, and no matter how the cleverest student replied, the scenarios would continue to be reshaped until there was no escape from admitting moral relativism. But after years of after-college study, I came to understand that those scenarios did not teach moral relativism. They actually served to prove there is an absolute moral law.

It is only because the absolute moral law exists that all those scenarios presented serious dilemmas. If there were no absolute moral law, then who cares! Let them die, kill them, torture them, grind them up, whatever. But you see, in the same way that absolute moral law is necessary for the relativist to manufacture moral dilemmas, or make comparisons about morality, or know he or she has been treated unjustly, absolute moral law is also evidenced by their ability to do so.

It is only because the absolute moral law exists that all those scenarios presented serious dilemmas. If there were no absolute moral law, then who cares! Let them die, kill them, torture them, grind them up, whatever. But you see, in the same way that absolute moral law is necessary for the relativist to manufacture moral dilemmas, or make comparisons about morality, or know he or she has been treated unjustly, absolute moral law is also evidenced by their ability to do so.

The classic philosophical arguments aren’t dissimilar from people using moral relativism to inject emotional cookie-cutter-arguments into abortion issues. The arguments are complex, pitting moral platitudes against each other, and they serve to confuse and bushwhack the unprepared. People can get confused and distracted; even make mistakes about complicated moral dilemmas, especially if they allow themselves to be trapped into viewing the dilemma from a single viewpoint. Where people may get confused in the distractions of emotional complications, they rarely make any mistakes about the basics—like how a well adjusted individual reacts when the tables are turned in a moral dilemma, or when some injustice is done to them.

Moral relativism might be extremely popular, and useful to the extent that people can avoid self-judgement, or any judgement about moral choices, but it’s wrong. In the same way that 2+2=4 for everyone in all places and at all times, absolute moral law, and absolute right and wrong are the standards by which all genuine moral choices are made. It’s self evident. What is right for you is also right for me, even if I find it inconvenient. The absolute moral law is not derived from personal wants and desires, or willful ignorance and self-denial. Moral relativism is a lie.